Bagging the Winter

Messier Objects

by Robert Bruce Thompson

010: Charles Messier

Good evening. For those of you who don’t know me, my name is Bob Thompson. My topic tonight is “Bagging the Winter Messier Objects”. I’ll tell you a little bit about each object, show you what it looks like, show you how to find it, and give you some observing tips. Priscilla tells me I have an hour. I haven’t timed this presentation, so let me know if I start to run over.

Incidentally, don’t worry about remembering the details or taking notes. All of this material, text and images, is posted on my web site, which is listed in the handout. I’ll be reading this material rather than speaking extemporaneously, because there’s so much detail to cover and I don’t want to misspeak or leave things out. If I do run out of time and you’re interested in the material I didn’t get to cover, you’ll find it on the web site.

Most of you are familiar with the Messier Objects, but there may be some newer members and visitors here who aren’t, so I’ll give you a little bit of background.

Charles Messier was a French astronomer who was active in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Messier loved comets—finding them, observing them, drawing them, and reporting new ones to his astronomer colleagues. They had an informal competition going as to who could find the most comets, and who could find each new one first. Every clear night, Messier was out under the stars in his Paris observatory with his small refractors—they ranged from 2” to 3.5”—looking for new comets. Back then, a 3.5” scope was good enough for finding deep sky objects, because Messier didn’t have to deal with light pollution. No streetlights or billboards plagued Messier. About the worst he had to deal with was the glare from candles.

Charles Messier was so famous for his love of comets that King Louis XVI called Messier his “comet ferret”. Messier was hung up on comets to the exclusion of everything else. In fact, Messier was pretty successful at finding comets. He discovered 21 of them by his own reckoning, and even by today’s stricter standards he would have been recognized as the discoverer of 14 or 15 of them, which is an incredible total.

But during his comet searches, Messier kept running into the same problem. There are a lot of objects in the night sky that look like comets but aren’t. The only way Messier could tell for sure if an object was a comet was to observe it over a period of time to see if it moved against the background stars. Messier wasted a lot of time looking at objects he thought might be comets, only to find out later they were star clusters, nebulae, or other objects—stuff that didn’t move.

To a guy who lived and breathed comets, this was intolerable, so Messier set out to make a list of these nasty objects so that he and other comet hunters wouldn’t be fooled by them in future. The irony is that no one remembers Charles Messier for the comets he discovered. Astronomers remember him for his list of objects to be avoided. And all of us now look at those objects, which are some of the most magnificent sights in the night sky.

Messier’s first list originally contained only 41 objects, but being the competitive guy that he way, he wanted to have more objects than another list that was published shortly before his own, so he padded out that original 41 with four more objects, including the Great Nebula in Orion, the Beehive Cluster (or Praesepe), and the Pleiades. All of those are naked-eye objects, so the only possible reason he had for including them was to reach the round number of 45 objects.

Messier kept expanding his list over the years until it eventually reached 103 objects. One of those was a duplicate, so there were really only 102 on Messier’s final list. During the first half of the 20th century, several objects that Messier had observed and written about, but not formally added to his list, were added retroactively. The complete Messier list now contains 109 or 110 objects, depending on who you listen to.

Incidentally, a lot of people wonder why Messier’s list stopped at 103 objects, ignoring many other DSOs including such prominent ones as the Double Cluster in Perseus. Messier continued observing for many years after adding his last object, but the short answer is that he could no longer compete so he stopped trying. William and Caroline Herschel and others had begun logging DSOs in a systematic way, using much larger scopes than Messier had access to, including what amounted to 18” and larger Dobs with focal lengths of 20 feet and more. When you’re outgunned that badly, there’s not a lot of point to trying, so Messier gave up.

020: Winter Messier Objects by Group

I’m talking tonight about the Winter Messier Objects, but that’s really an arbitrary distinction. Most sources divide the Messier Objects into four to six groups based on seasons, but there’s no general agreement as to which objects belong in which group. In fact, at our latitude at least three-quarters of the Messier Objects are visible any clear night of the year, although you’ll have to start early and finish late to view them all.

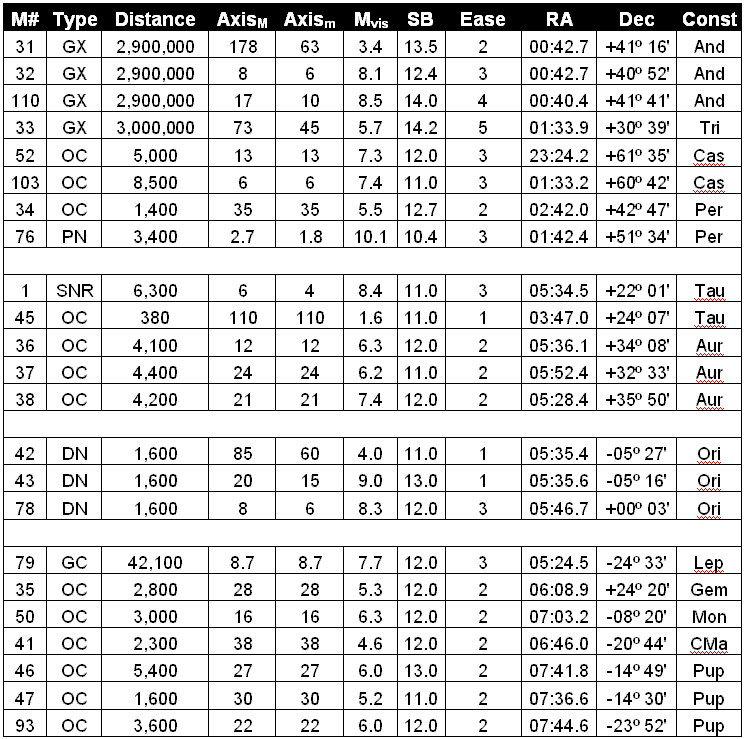

I’ve chosen to use the Astronomical League’s Winter Messier Group, presented in their order. The AL list of Winter Messier Objects includes 23 objects, or just under a quarter of all the Messier Objects. There’s quite a variety of object types, including one Supernova Remnant (SNR), one Planetary Nebula (PN), four Galaxies (GX), one Globular Cluster (GC), three Diffuse Nebulae (DN), and no less than 13 Open Clusters (OC).

There are twelve constellations represented, including one object each in Canis Major, Gemini, Lepus, Monoceros, and Triangulum; two objects each in Cassiopeia, Perseus, and Taurus; and three objects each in Andromeda, Auriga, Puppis, and Orion.

Some of the columns on the chart deserve a brief explanation:

- Distance – the true distances of most Messier Objects are not known with much precision. For example, various sources give the distance of the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, as between 2 million and 3 million light years. The distances I’ve given are those supplied by SEDS, which is also the source of much of the other data on the chart.

- Major Axis and Minor Axis – The apparent visual size of an object, given in arcminutes. Where those dimensions are identical, the object is circular, such as a globular cluster. Size is rather arbitrary, because the visible extent of many objects depends on the size of your telescope, the darkness of your skies, the quality of your night vision, and your level of observing experience. In a small telescope, only the central core of an object may be visible, leading to a relatively small visible extent. In a larger scope, much more of the object may be visible.

- Visual Magnitude and Surface Brightness – Although visual magnitude can be measured with great precision for stars, which are point sources, that is not the case for extended objects like the Messiers. The visual magnitude given for an extended object assumes that all of the light emitted by that object has been compressed to a point source. Magnitude can vary significantly from source to source according to how much of the full extent of the object is included and how the integration is done. For example, the listed magnitude of M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, ranges from 3.4 to 4.8, depending on which source you accept. Surface Brightness, on the other hand, attempts to give an average luminance value over the full extent of the object. In the case of objects that comprise a few bright sources covering a relatively large area of sky, magnitude and surface brightness can differ dramatically. For example, the magnitude of M45, the Pleiades, is usually given as about 1.6, while the surface brightness is around 11. Large objects with low surface brightness are very hard to see. That’s why M33, the Triangulum Galaxy, which has the lowest surface brightness in this group at 14.2, is so hard to see, particularly from a site like Bullington that suffers from some light pollution.

- Ease – this is my composite rating, based on how easy an object is to find and how easy it is to see once you’ve found it. My ratings range from “1”, which means very easy, to “5”, which is quite difficult. Again, these ratings are personal. They assume a 10” scope at Bullington, being used by a moderately experienced observer. If you’re an experienced observer using a larger scope from a dark-sky site, many of these objects are even easier than I make them out to be. On the other hand, if your scope is smaller, or if you have little experience, even some of the objects I call easy may be quite difficult for you to find the first few times. If so, don’t get discouraged. We’ve all been through that, and it does get better.

Before I get started on the objects themselves, I wanted to talk a little bit about how to find and view them. Some of these objects, like M45, The Pleiades, are naked eye objects. Others are visible in binoculars and finder scopes, and still others are only visible in your main scope. Incidentally, believe it or not, there are some objects, particularly large, dim ones, that are actually easier to view with binoculars than with a telescope. Everyone has his own way of finding things, but for those of you who aren’t experienced at finding dim objects, I’ll explain how I do it. There may be better ways, but this works for me.

For dim objects, my first step is to locate the object on a star chart and try to orient it using bright stars and constellations as guideposts. Once I’ve done that, I often use my binocular to locate the object—assuming that it’s visible in binoculars—getting an idea of where it is relative to other brighter objects within the binocular field of view. I then construct a mental image of the geometric relationship between the location of the object and the locations of nearby bright stars.

Once I have a feel for the object location, I use my Telrad finder to point the main telescope to the right general vicinity. Once I get the brighter guideposts stars lined up properly in the Telrad, the object I’m looking for should be near the center of the Telrad field.

If the object is in the Telrad field of view, it should also be somewhere in the field of view of my 8X50 finderscope. Except for the dimmest objects, I can usually see the object itself in the finder scope, although many objects are just gray smudges. But if I can see a smudge, I can center it in the finderscope crosshairs, which puts it into the field of view of the main scope.

I start out using a low-power eyepiece in the main scope. In my case, that’s a 30mm Orion Ultrascopic, which yields about 42 power in my 10” Dob. That eyepiece in that scope yields a true field of view of about 1.33*, which is to say almost three times the width of the full moon.

Where I go from there depends on the object I’m viewing. Many Messier Objects are quite large. Some, in fact, are so large that they won’t fit into the field of view of my lowest power eyepiece. For those objects, my only alternative is to pan the scope back and forth to take in the entire object or use my binocular. Other Messier Objects are tiny, and you can use some serious power on some of those. Most Messier Objects fall into one of three categories:

- Very Large – objects like the Andromeda Galaxies, the Triangulum Galaxy, the Pleiades, and the Great Nebula in Orion. You find and view these objects with your widest eyepiece—2 degrees or more is ideal—although you may resort to a medium- or high-power eyepiece to drill down into the details, such as the Trapezium in M42. For example, in our 10” f/5 Dob, which has a focal length of 1255mm, I use an Orion Ultrascopic as our wide-field eyepiece. That provides a true field of view of about 1.33 degrees, which is excellent for locating and viewing large objects. Once I have the object centered, I’ll use our 14mm Pentax XL, which yields 90X and just under ¾ degree true field, to view the details. For really fine details, like the Trapezium, I’ll Barlow the Pentax XL to 7mm and 180X.

- Moderate – many of the Messier Objects we’re considering tonight, particularly open clusters, fall into this category. They’re more or less the size of the full moon. You use your low-power, wide-field eyepiece to find these objects, and then use a medium power eyepiece to view them. The ideal eyepiece for viewing these objects is one with a true field of ¾ degree or so.

- Small to Very Small – this class includes objects like planetary nebulae, many globular clusters, and very remote galaxies. Once again, use your lowest-power, widest-field eyepiece to locate these objects, although you may have to move up to a medium-power eyepiece to verify that you have them. Some of these don’t look like much more than a fuzzy star in a low-power eyepiece. Once you have them centered in your field of view, you pile on as much power as they’ll take, and even then they may appear pretty tiny.

Incidentally, if you don’t have a Telrad, that doesn’t mean you can’t find these objects. It just means your job will be harder. Most deep sky enthusiasts will tell you that buying a Telrad was the best $40 they ever spent. A Telrad is pretty useless under bright skies like those in Winston-Salem, but if you can get to a site with reasonably dark skies, like Bullington, you’ll find that having a Telrad makes it about ten times easier to find objects than just using your optical finder. But don’t discount the value of an optical finder. You really need both a Telrad and an optical finder, ideally something like an 8X50, to make finding objects as easy as possible.

Keep in mind when I talk about the appearance of the objects that Barbara and I do most of our observations from Bullington with a 10” Dob. If you have a larger scope, or if you observe from a darker site like one of the Parkway sites, you’ll get better views. Conversely, if you have a smaller scope you’ll see less detail. I was going to add “or if you have brighter skies”, but the truth is that Bullington is about the brightest site that you’d want to try to observe many of the Messier Objects from. From any place brighter, like most areas of Winston-Salem, the background light pollution will overwhelm the dimmer Messier objects, making them impossible to see even if you can somehow get them into your eyepiece.

Okay. Enough of the preliminaries. Let’s get to the objects themselves.